In the The International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade we are invited to reflect on the historic role that African societies in diaspora play in our contemporary societies.

By: Manuela Tenreiro Author of the online course African Art

International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

The importance of African cultures in diaspora to contemporary societies led the United Nations to declare 2015 to 2024, The International Decade for People of African Descent, under the topics recognition, justice, development and intersecting forms of discrimination.

World nations, particularly those of Western Europe and the American continent, took up the responsibility of creating legislation to fight intolerance, racism and xenophobia.

In that context March 21st was proclaimed International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, and today, March 25th, marks The International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

The historic role that African societies in diaspora play in our contemporary societies

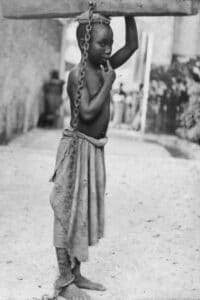

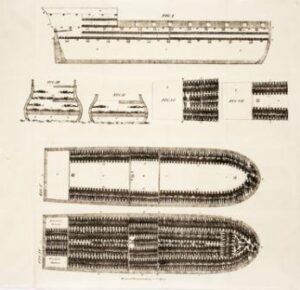

The specific reference made to the transatlantic slave trade that occurred for nearly 400 years, between the 15th and 19th centuries, commemorates around 12.5 million Africans victims of slavery taken from their land and their family, sent to unknown, hostile territories, subjected to an unprecedented slave-based system.

The victims of slavery were the backbone holding the wealth and profits that developed the West, making way to the Industrial Revolution and, consequently, the economic inequalities dividing Europe and Africa to this day.

English Slave Ship, 1822

The “Luso-tropicalismo”

Knowing this history is essential to a better understanding of how the modern world came about, and to promote the appreciation for African cultures both at their origin and in diaspora.

Knowing this history is essential to a better understanding of how the modern world came about, and to promote the appreciation for African cultures both at their origin and in diaspora.

In Portugal, this was still a sensitive topic just a few years ago. It still is.

Many Portuguese do not appreciate being confronted with a history that turns them from heroes to villains.

The sociology behind such attitudes is as interesting as Luso-Tropicalismo – the theory which explains it – created by Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre, a good fit for Salazar’s Estado Novo as it served perfectly the empire’s discursive strategy in response to post WWII anti colonial movements.

What is the Luso tropicalismo

Summing up, Luso-Tropicalismo build up on aspects that resonate to many Portuguese as historical facts: the ability of the Portuguese to adapt to tropical settings, their ‘benevolent’ and ‘paternal’ attitude towards ‘others’ at different levels of primitivism, their trailblazing bravery, their love for black and indigenous women, or, their evangelizing mission, their gift of ‘new worlds to the world’.

A vision of history

This was a history where Africans belonged in the set of Gone with the Wind, to a overprotective family (who protected them even from their own freedom, to which they were supposedly unprepared).

A history about the victims of slavery written as a long succession of men capable of great deeds, celebrated in the art of the Monument of Discoveries (1940) or in official national exhibitions such as the Commemorations of the 500th anniversary of the death of Infante D. Henrique (1960).

Finally, a history actively promoted by the Estado Novo to the point of censoring any other version, as learned British historian Charles Boxer, banned from researching Portuguese archives after the publication of his Race Relations in the Portuguese Empire (1964).

Read more about Luso-tropicalismo in this article by researcher Cláudia Castelo.

African Diaspora Studies

In spite of the fact that the Estado Novo regime ended half a century ago, textbooks did little to change the narrative about the victims of slavery , and the regime’s propaganda was perpetuated in the classroom generation after generation.

The word ‘slave’ pops up casually, inserted in a list of products such as spices and precious metals, lost among merchandise and stripped of humanity.

Fair enough, slaves were considered as such, but that does not justify that current textbooks keep a mechanism of (not) telling a story, not further knowledge, and ideally encourage self-reflection.

Studies and reflections in other countries

Such lack of knowledge of an important part of our own history strongly contrasts with other countries that have a slave-based past, and where African Diaspora Studies are decades ahead, particularly in regards to the American continent.

Brazil, the United States and the Caribbean comprise what author Paul Gilroy termed ‘Black Atlantic’, where African continuities are punctually syncretized with European, native-American and even Asian influences, or remain practically intact, in a resistance of memory of the victims of slavery , like in the songs of cuban Francisco Aguabella, which can be traced along the Brazilian coast and across the ocean to western Africa.

Coming soon, Citaliarestauro.com will publish a new course dedicated to this fascinating history and entitled Arts and Cultures of the African Diaspora.

The African presence in Portugal

In spite of Portugal’s academic deficiency regarding slave trade studies and the African diaspora, there is abundant evidence of the African presence in the territory as far back as the Middle Ages – even though the perception of the public is that previously to the 1974 revolution, there were no significant masses of people of African descent in the country.

From Zurara’s horrific description of the arrival of sub-Saharan African captives to Lagos in 1444, to the representations of black people along the centuries, the descriptions of foreign travellers, such as Italian João Baptista Venturino who, in the 16th century, wrote about the ‘breeding’ slave quarters at the infamous Bragança Palace, the fact is that, although African presence in Portugal was massive and visible to everyone, in post-revolutionary Portugal, we know nothing about the victims of slavery .

Studies and projects

In the last few years, Isabel Castro Henriques, pioneer professor of African Studies since 1974, has conducted research on the African presence in Portugal throughout history, and other researchers such as Marta Araújo (Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra) and Cristina Roldão (Education School at Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal), have done a remarkable work to bring that hidden history to Portuguese education.

Similarly, an Afro-Portuguese new generation are stirring up Portuguese culture associating and collaborating in literary, artistic and political projects.

Some examples are Djass – Association of Afro Descendants, founded in 2016 to fight racism and to promote equality and diaspora culture; INMUNE – National Institute for the Black Woman, dedicated to the intersectional issues that cross gender and racial discrimination; Batoto Yetu Association, which promotes African culture, particularly dance and music, among Afro Portuguese youths; or, the Djidiu group, storytellers, put forth by Carla Fernandes who also founded AfroLis radio.

African contribution to Portuguese culture is beginning to get the attention it deserves…

Thanks to the work of these and so many more individuals, African contribution to Portuguese culture is beginning to get the attention it deserves. Soon, Lisbon will be home to a Memorial to Slavery, planned for this year at José Saramago Square (where there was once a slave market).

Created by Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda, the monument is a massive sculptural ensemble alluding to the sugar plantation. In the last five years, similar projects to the Black History Walks in London or the Black Heritage Tours in New York, were created.

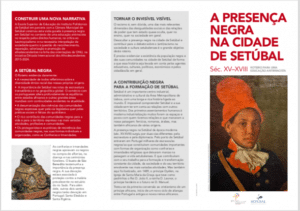

The most recent was the tour Black Presence in the City of Setúbal. In 2016, two other initiatives were launched: Lagos in the Slave Route, and Spaces of the African Presence in Lisbon created by Batoto Yetu Portugal and based in the books by historians Isabel Castro Henriques and Pedro Pereira Leite (download here – Portuguese only). Also in Lisbon, those interested can also take the African Lisbon Tour organized by Naky Gaglo, who came from Togo to Europe and fell in love with this history of African Portugal.

In homage to the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade, when we try to draw attention to a history we mistreated for so long, Citaliarestauro.com wanted to introduce to its readers the research work done on the secular African presence in our country.

African culture in Portugal adds value to our own history, stimulating and enriching it, and must be at last represented and made visible in our textbooks, our knowledge, and specially our recognition of the role of Africans in our own development and cultural wealth.

As witness to that heritage, below we share a short documentary on an African tradition in Portugal retrieved from a time when Fado was danced.

African art – from rock art to modern era

Online course about the history of art in Africa

Manuela Tenreiro

PhD in History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies, I specialized in Arts and Cultures of the African Diaspora in 2008. Previously, I obtained a bachelor degree in visual arts and photography from San Francisco State University, while working as a docent at Diego Rivera’s Pan-American Unity mural (City College). Creator, editor and translator of the online publication conTRAmare.net while residing in Brazil between 2008 and 2017, I collaborated in various editorial and art education projects, as a writer, translator and researcher. In Rio de Janeiro, I attended Literary Translation courses and the Advanced Program of Contemporary Culture at the city’s Federal University. In 2017, I returned to my hometown, Lisbon, where I manage a private art studio with women artists and develop projects writing and translating art history projects.

1 Comment.

Hello 🙂 I just want to tell you that I am all new to blogging and certainly savored your web page. Very likely I’m want to bookmark your blog post . You definitely come with terrific articles and reviews. Thanks a bunch for sharing your web site.