‘In Sumer, a good millennium before the Hebrews wrote the Bible and the Greeks the Iliad and the Odyssey, we already find a whole rich literature flourishing, comprising myths and epic narratives, hymns and laments, and numerous collections of proverbs, fables and essays. It is not utopian to predict that the recovery and restoration of this ancient and forgotten literature could well be one of the greatest contributions of our century to the knowledge of mankind’. (KRAMER, 1997: 18).

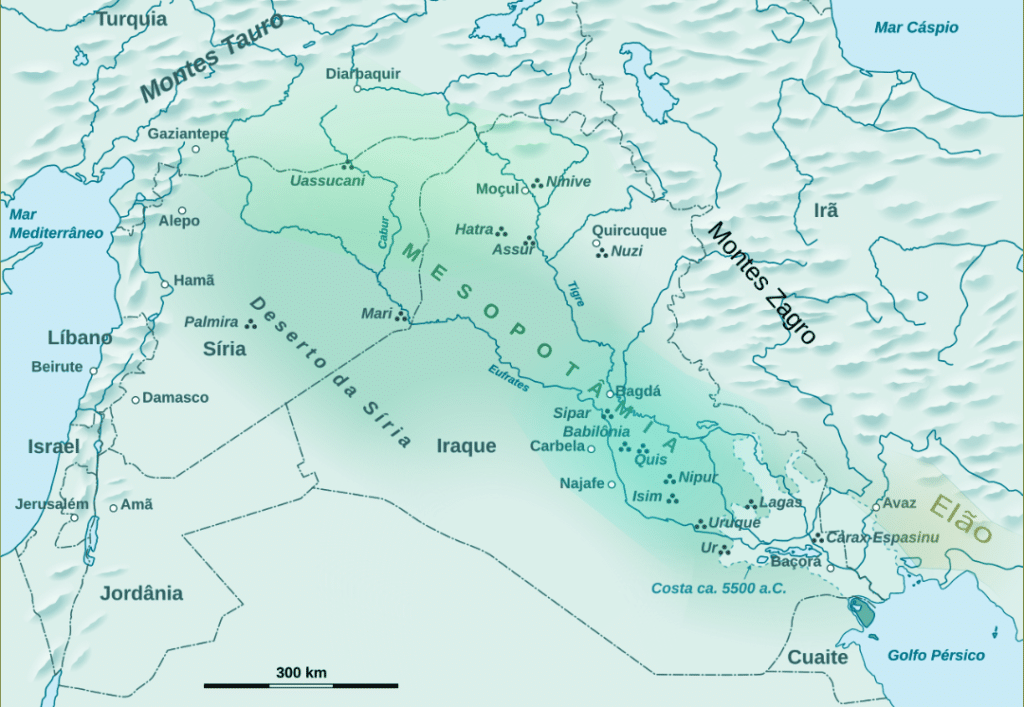

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a territory located between the twin rivers Tigris and Euphrates in the Near East, occupied by various peoples in ancient times, including the Sumerians, Assyrians and Babylonians, and is heterogeneous in character, not unified as a country.

The cultural legacy of Mesopotamia began to take shape with the Sumerians, through the invention of cuneiform writing, and the consequent transition from prehistory to history. Their legacy reached a strong projection in the civilisations that followed them and even in today’s societies; widespread notions on which this text reflects.

The Civilisation of Mesopotamia

Kramer (1997) conveys two notions. The first shows that social, economic and political development promotes peace and cohesion, which results in intellectual flourishing. These characteristics make up the set of criteria that define a properly organised civilisation. Secondly, that these circumstances are not exclusive to modernity, as he makes clear in his work ‘History Begins in Sumer’.

The cultural legacy of Mesopotamia

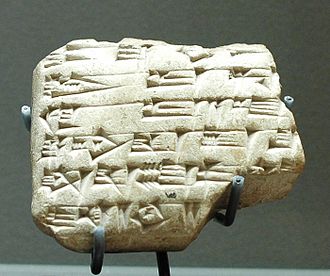

Cuneiform writing

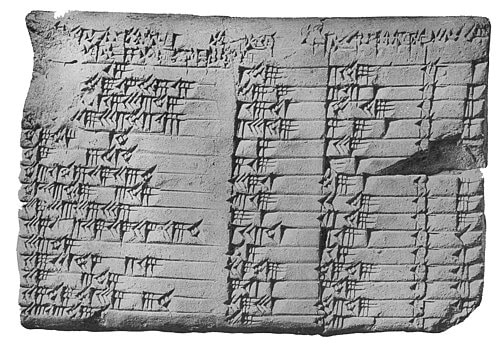

When archaeological discoveries in the 19th century revealed that the peoples of Mesopotamia as long ago as 3000 years BC, had a cuneiform writing system, on clay tablets, developed and widely used to record, organise and develop their daily lives in various aspects, it not only made it possible to study the civilisation itself, but also proved that the contribution and influence of their knowledge was decisive for the civilisations that followed.

In this way, these tablets provided an essential documentary archive for understanding the cultural spectrum of this civilisation over time, revealing the foundations of religion, literature, law and sciences such as astronomy, geography, mathematics and medicine.

Each of these niches of knowledge now deserves a brief reference that demonstrates what has been said so far.

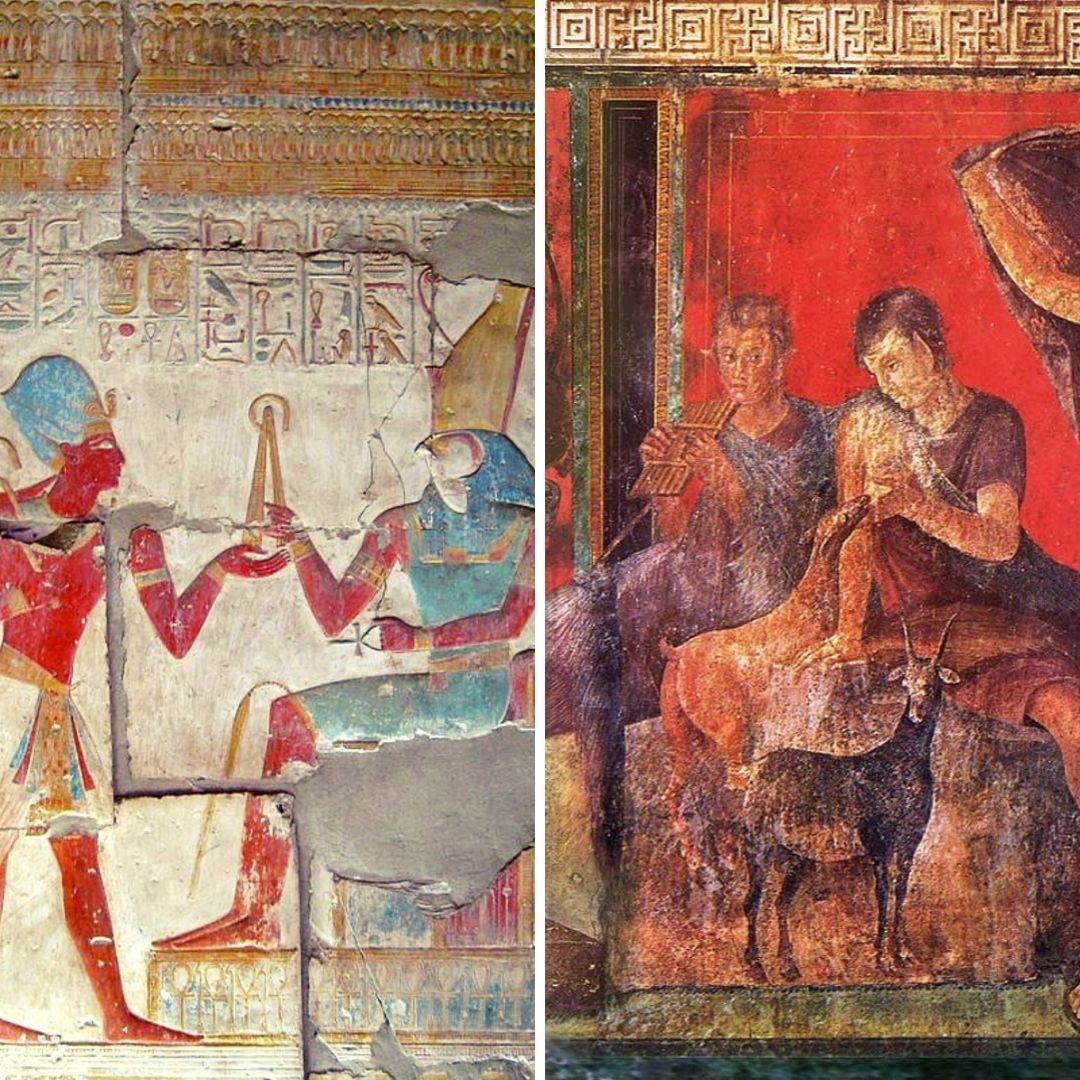

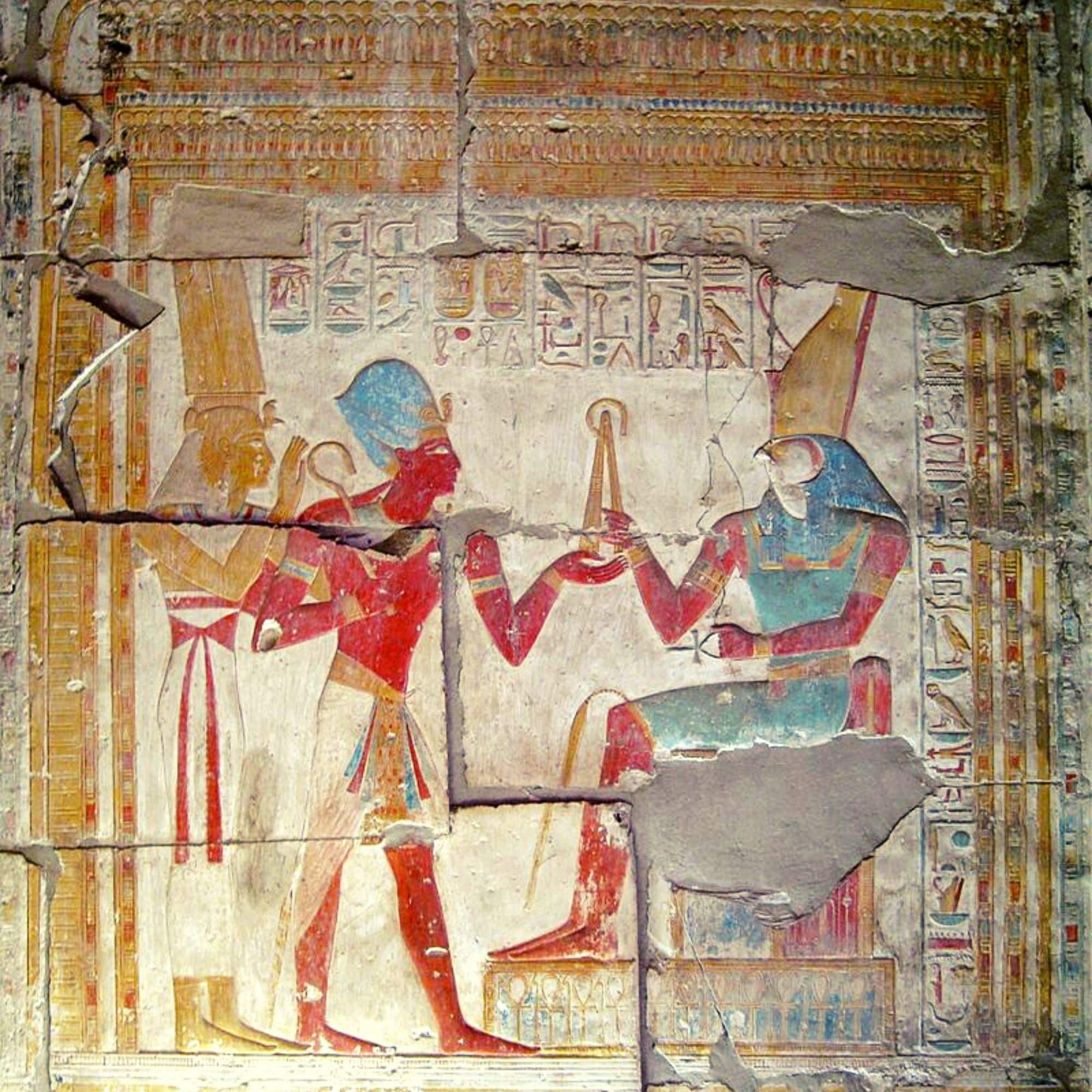

The religion of Mesopotamia

In religious terms it is known that the Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians (the peoples who succeeded the Sumerians and took power in Mesopotamia) assimilated the Sumerian deities in the form of a cosmic triad, made up of the god of the sky, An, the god of the atmosphere, Enlil, and the god of fresh waters, Enki-Ka, who coexisted with the astral deities of the sun, Shamash, and the moon, Sin. The gods were conceived similar to men except in immortality.

These peoples developed cosmogenic myths that explained the origins of the gods, the world and mankind. The most famous was the poem Enuma Elish, which exalts the Babylonian god Marduk, who supplants Enlil and becomes the main ruler and sovereign of the universe. Some of these notions are analogous to current religious doctrines, such as the concept of the divine trinity, heavenly immortality and the similarity between gods and men.

Literature of Mesopotamia

As far as literature is concerned, Gilgamesh is the oldest known epic. It was found in the library of Assurbanipal in Niniveh and tells of the adventures of the king of Uruk in search of immortality. A fact that attests to the difference between men and gods. This literary model, the epic, would come to be used by classical civilisations, exerting a strong influence on the Iliad and the Odyssey.

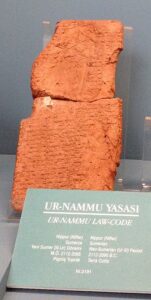

Law in Mesopotamia

As far as legislation is concerned, Mesopotamia is known as the homeland of written law in Pre-Classical Antiquity, with the Code of Hammurabi (1728-1686 BC) standing out as the most famous, although it is a successor to earlier codes such as that of Ur-Namu (2050-2032 BC), Lipit-Ishtar (1875-1865 BC) and of Eshnuna (1825-1787 BC).

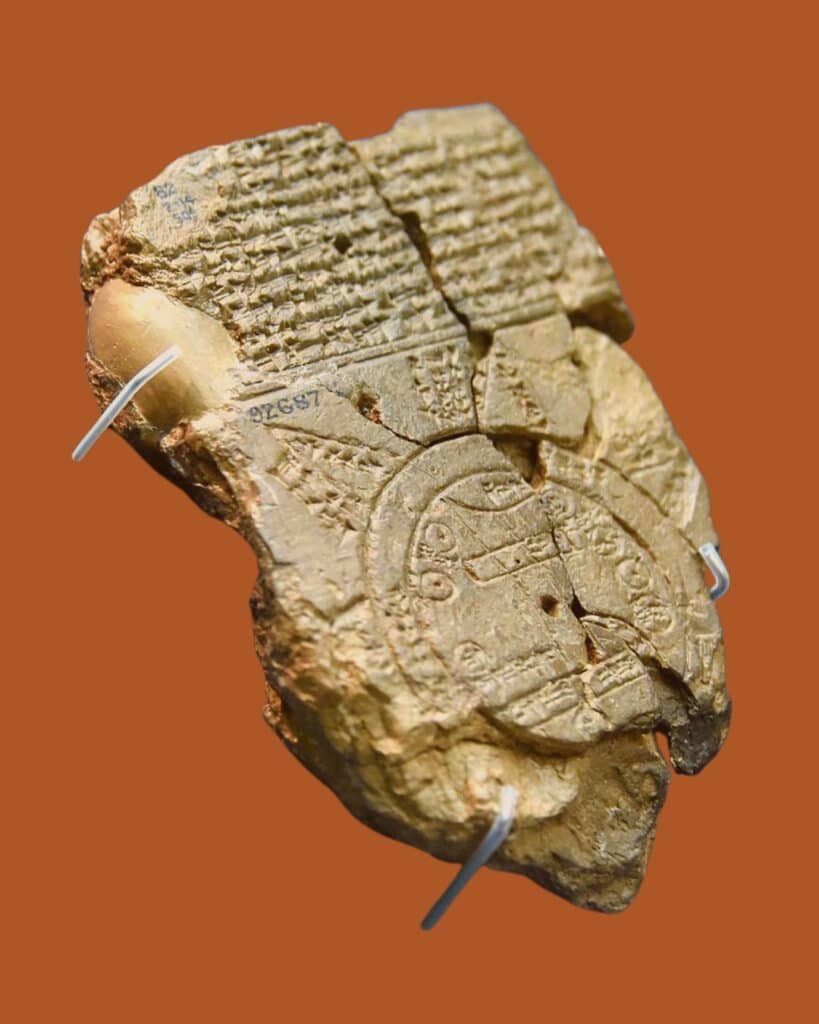

Geography in Mesopotamia

As far as Geography is concerned, the school learning programmes about rivers, mountains and countries stand out, as well as the existence of a world map from the 6th century BC where the Earth is represented as a disc with Babylon in the centre.

Maths and Astronomy in Mesopotamia

Maths achieved greater development than Geography with the sexagimal system, dividing the circumference into 360º, the hour into 60 minutes and the minute into 60 seconds. Clay tablets from the 2nd millennium also reveal tables with numbers for division and multiplication, and one of them, from the 18th century BC, graphically illustrates the Pythagorean Theorem.

The development of astronomy from 500 BC provided the lunar calendar that divided the year into 12 months and twenty-nine days, starting with the first new moon, which followed the spring equinox. They also divided the week into 7 days when they established the seven great sidereal gods: the Sun, the Moon and the five planets visible to the naked eye, which would be attributed to each of the days of the week by Western peoples.

Medicine in Mesopotamia

The sanctions imposed on doctors in the event of failure (in the Code of Hammurabi), some recipes, types of medicines (purgative drinks, washes, ointments, dressings, poultices, ointments, pills, suppositories and fumigations) are known about medicine, some records of operations carried out on patients, assertive diagnoses of Jaundice and Epilepsy, the location of the school where physicists were trained, such as Nipur, as well as the most common place to practise their trade, such as dark and isolated rooms.

However, these peoples were also devoted to the belief in the properties of magic, often complementing recipes or recommendations with practices such as exorcism or incantations, or using ingredients such as urine, excrement, blood and sperm.

Conclusion on Mesopotamia’s Cultural Legacy

Finally, a note: in addition to Mesopotamia’s cultural legacy and the fundamental principles of Western science, we also owe Mesopotamia some institutions, such as the crowning of kings, some religious symbols like the lunar crescent, some words like cane (qânu) or alcohol (guhlu) and the presence of Mesopotamian episodes in the Bible, such as the fall of the Tower of Babel or the Flood.