Artemisia Gentileschi is undeniably one of the great representatives of Baroque painting although she was forgotten in art history textbooks for a long time.

From 1970 on, and associated with the feminist movements, Artemisia Gentileschi was rediscovered.

Her life, marked by the courage to denounce the rape she suffered in 1611 (at the age of 18) and to confront the society of the time, led several authors to develop studies on Artemisia, her life and her work.

In this article we propose you to get to know this great artist of Baroque painting who was the first woman accepted into the Florence Academy of Fine Arts.

As you will see, her works of art reflect the strength and energy characteristic of Baroque painting and the artist’s enormous genius.

Text Rute Ferreira. Author of several online courses in the field of Art Analysis and Art Curatorship.

Artemisia Gentileschi – the beginning of the artist’s career

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593.

Her father was the painter Orazio Gentileschi, an important artist of the time, who worked mainly with religious themes and landscapes.

Around 1580, Orazio moved to Rome, where he went to work alongside Agostino Tassi, a well-known landscape painter of the region.

Both began to work together frequently, and became friends.

From an early age, Artemísia began to study art with her father.

Like him, the painter was influenced by Caravaggio, one of the most important artists of the Baroque, “an art that combined emotion, dynamism and drama with intense colors, realism and strongly contrasting tones¹”.

Suzana and the Elders – 1610

One of the works Artemísia produced while still in her teens, at the age of 17, was the painting Suzana and the Elders, from 1610.

In it, the artist narrates a moment of history that appears in chapter 13 of the book of Daniel, which appears in Catholic Bibles (for Protestants, the text is considered apocryphal).

Artemisia Gentileschi Suzana and the Elders 1610

In the story, Suzana is a beautiful woman, married to a very rich man named Joaquim, who arouses the interest of two judges, who agree on how they will possess her.

One day, as she is preparing to bathe in her garden, they throw themselves on her, saying:

“We burn with love for you. Accept and give yourself to us. If you refuse, we will denounce you: we will say that there was a young man with you, and that is why you made your handmaidens leave.²”

Suzanna would rather die than give herself to them, and asks for help. This, of course, causes her to be judged.

In Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting , the sexual approach of the judges is shown as a traumatic event.

Artemísia Gentileschi: the rape

Artemisia lost her mother at the age of 12 and lived surrounded by male companionship, her father and brothers.

She had a close friend named Tuzia, who lived upstairs in her house, rented by Orazio.

In 1611, when the artist was 18 years old, her father was still working with Agostino Tassi, decorating the vaults of a palace.

Orazio hired him to give Artemisia painting lessons, so that she could develop her technique.

And it was Agostino Tassi who, during Orazio’s absence, raped Artemisia.

It wasn’t until almost a year later that the case came to light, with the complaint filed by Artemísia’s father, who also accused Tassi of stealing a painting from him.

Artemísia Gentileschi: Who was judged?

Despite the complaint against Tassi, Artemisia also had to go through a trial: because if she hadn’t been a virgin before the rape, her family would not have had the right to press charges.

In Artemisia’s statement, she said that Tassi found her working on a painting and abruptly took the brushes from her, telling Tuzia, Artemísia’s friend, to leave.

Artemisia begged Tuzia not to leave her, but it was no use, and she was left alone with Tassi, who took her to her room and locked the door.

Danae

One of the artist’s works depicts the Myth of Danae – the rape perpetrated by Zeus that led to the birth of Perseus.

Artemisia Gentileschi Danae 1612

Learn more about the myth of Danae here.

The testimonials

He threw me over the edge of the bed placing one hand on my chest, he placed one knee between my thighs so that I could not close them and lifting my clothes, which he made a great effort to lift, he placed a handkerchief around my throat and mouth so that I could not scream and the hand as before he held me back with the other hand he left me, having that one before placed all two knees between my legs and pointing the member to my nature [vagina] began to push and put it inside that I felt that it burned me strong and made me great evil that by the impediment that held me to my mouth I could not scream, I also tried to scream as best I could calling for Tuzia. And I scratched his face and pulled out his hair and before getting it inside I still gave him a painful squeeze to his member and pulled out a piece of flesh, with all this he did not consider anything and continued TESTIMONIAL OF ARTEMÍSIA GENTILESCHI³

The trial was controversial and public opinion turned against Artemisia and in favor of Tassi, including Tuzia testifying against her.

Nevertheless, the painter was found guilty and on November 27, 1612, Tassi was sentenced: 5 years of forced labor or leave Rome. The painter evidently preferred exile.

Artemísia Gentileschi: arranged marriage and court painter

To “restore Artemisia’s dignity,” her father arranged her marriage to a painter named Pierantonio Stiattesi and the couple left for Florence, where she became distinguished as an excellent court portrait painter.

Artemisia was a well-connected woman, having the respect of Florentine society.

Her contacts included the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Charles II of the Medici, the scientist Galileo Galilei, and the family of Michelangelo Buonarroti.

An artist of undoubted ability, she was the first woman to be accepted into the Florence Academy of Fine Arts, and in 1638, she joined her father at the court of King Charles I, by invitation of the king himself, who admired Artemisia’s work.

She died in 1656.

Want to learn more about art analysis and art history?

Get to know the online courses

Pigments in art restoration and research + History of pigments in art 2 online courses

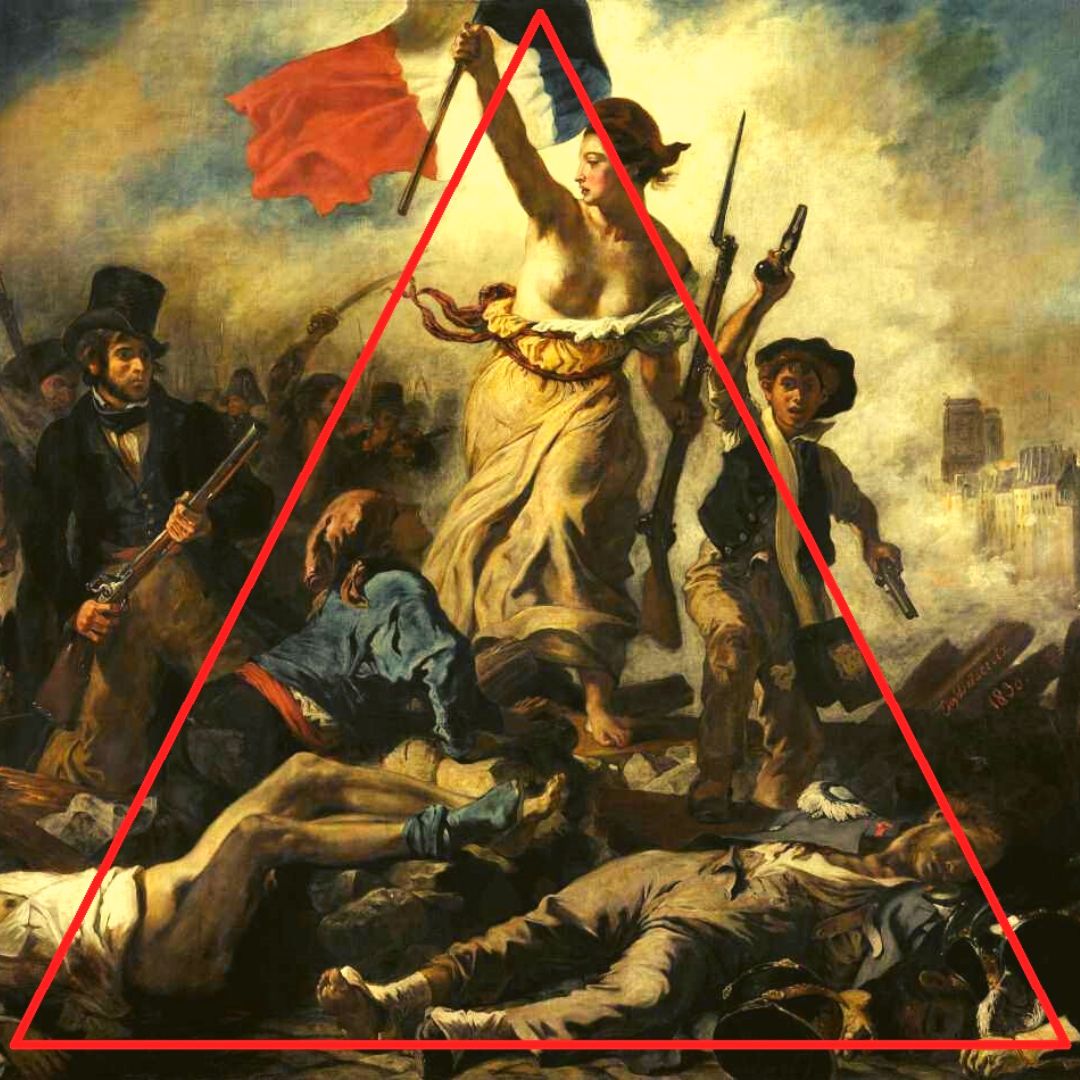

Interpretation of masterpieces of Neoclassicism and Romanticism

Credits and references

Images – Wikiart.org

¹ Hodgie, Susie. Breve História da Arte. São Paulo: Gustavo Gili, 2018.

From Atti di un processo per stupro: the interrogation of Artemisia Gentileschi from the point of view of gender, by Cristine Tedesco. Cohen, E. S. (2000). The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History. The Sixteenth Century Journal, 31(1), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.2307/2671289

1 Comment. Leave new

You need to take part in a contest for among the finest blogs on the web. I will advocate this website!